The lights are hot and bright. I'm doing the buttons while trying not to disturb the crisp, structured fabric. I'm shopping for a great white shirt. The ones I have don’t suit what I'm dressing for. I look up, the seam hits the shoulder the way I want it to, but now I don't know what to do. How do I wear it?

I'm shopping because I don't want to dress for where I am, but where I'm going.

Grown, but not boring. Professional, not bland

The way we dress is a language. It tells stories of who we are, who we wish to be and where we want to belong. Some are fluent, others study, and some adopt a fake accent. Even those who claim not to partake do. Rejection is still a signal. Everyone’s in the conversation.

Being concerned about clothes is often dismissed as frivolous or reduced to who has what. That is missing the point.

The way we dress matters because people interpret what they see. We place others in mental groups based on dress, posture and what we think that means. Everyone carries visual markers of their social “types”.

If you pay attention, you learn the looks. When I had a mullet with baby bangs, topped with my septum piercing, anyone could tell I went to a liberal arts college.

I call them social uniforms.

We deny that we wear uniforms because they feel conformist (and we're special). Yet people categorise us by how we dress, regardless. Once we accept that, we can start using it in our favour.

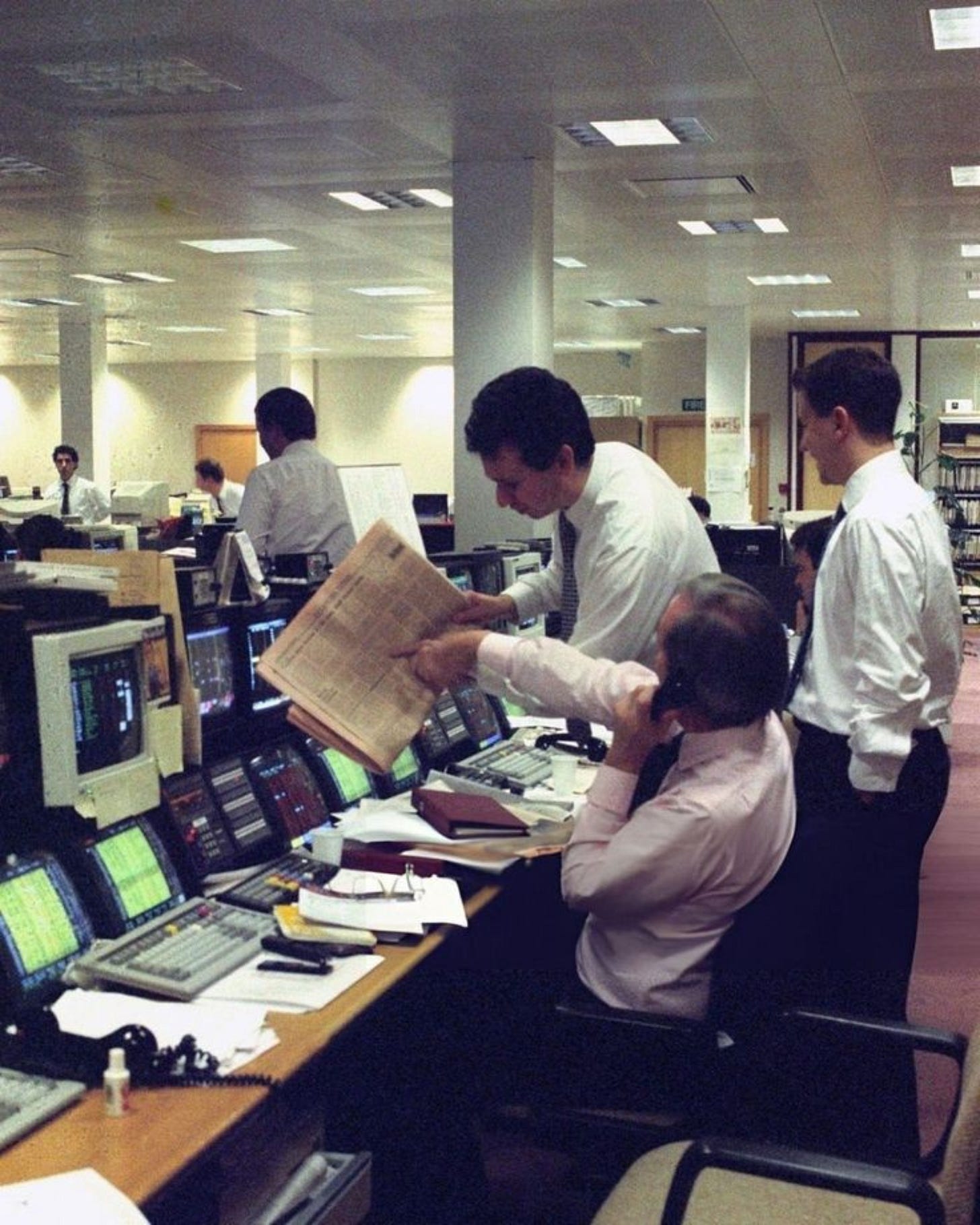

I want to dress for the rooms I plan to enter. What stopped me before was who I associated the shirts with: The Baby Blues - corporate men in their signature pale blue uniform. They represented a club I wasn't invited to and never saw a future within.

Now, I kind of do. But in my way.

The Rules I Didn’t Know I Was Breaking

I’ve always dressed for my current context, never beyond my current position. Partly because I didn’t know where I was going, partly because I didn’t know how.

I can still feel my chest burning whenever I remember someone doing me a favour and pointing out that I was not appropriately dressed in a photo I used professionally. It showed too much skin. I had no idea my shoulders would attract the scarlet A of the corporate world (okay, there was collarbone). That burning feeling was the familiar shame of having unknowingly broken another social rule.

To me, it was more important that it wasn’t a selfie, that I looked put together, straight into the camera, sober. But those aren't the standards that count.

This taught me that you must know the rules; if you do, you can crop to your heart's content.

Habitus – The know-how

To feel better about my blunder, I rationalise my mistake by thinking of Bourdieu’s concept of habitus. Habitus is the internalised set of habits, tastes and ways of being that we gain through our social position and experiences. Within a particular habitus, members tend to think and behave similarly, like wearing similar clothes or developing a liking for natural wines.

It looks like intuitively knowing what to wear, how to behave, and what counts as "good taste." That’s why going to the ‘right’ schools or spending time around people who are in the know gives you an advantage. It might look like merit, but it's inherited privilege.

I'd never been exposed to the corporate world. It was still a foreign language. My mistake was not a personal failure; I was learning the rules.

Our habitus shapes our choices, preparing us with the skills and confidence to navigate familiar environments. That’s why entering a new one can feel disorienting. The more time we spend in a place or with certain people, the more we absorb the conventions of dress, speech and belonging.

Social uniforms don’t have to cancel individuality if you dress with intent instead of defaulting to a costume.

How We Read Each Other

I think of social uniforms as recipes for personalities. Mix Uniqlo and Arket, with a splash of Cos, and you have a young professional. Add funky frames, a headpiece or something that says, "in with the cool kids," and you have a creative director. There are endless examples, but I have an argument to make.

Our clothing choices blend personal and group identity, so what we wear becomes a social shorthand for belonging and qualification. Sociological studies back this up: strangers respond to what the uniform represents, not the individual.

Whether we feel aligned, included, or excluded determines if we adopt the style. This is where I got in my own way. I didn't consider corporate dress because I falsely believed that associating with a group through its symbols meant full submission to its terms.

That belief kept me out. But my motivation has shifted, and so has my perspective.

I’ve since learned that dressing for the room doesn’t mean dressing for assimilation, but a way to take space in a language they understand. I am not looking to belong. I want to be considered. To do so, I must, to some degree, follow the script.

This logic doesn’t have to be suppressive. It can be a creative way of paving our path within our constraints. The uniform can be a tool, not a straitjacket. We wear it to express cultural awareness, and style it to feel like ourselves.

Recognising these dynamics reveals the hidden norms people live by. The more I understand them, the more consciously I can engage. It gives me agency, which lets me be creative.

I want to actively participate in life and the world I move through rather than being passively placed by it. That’s why I’ve always used the way I dress as a tool. I have used it to hide by fitting in, to feel accepted by looking good, and to express myself creatively. But it’s the first time I am using it to realise my future.

Social uniforms don’t have to cancel individuality if you dress with intent instead of defaulting to a costume.

Black Ivy – a case study

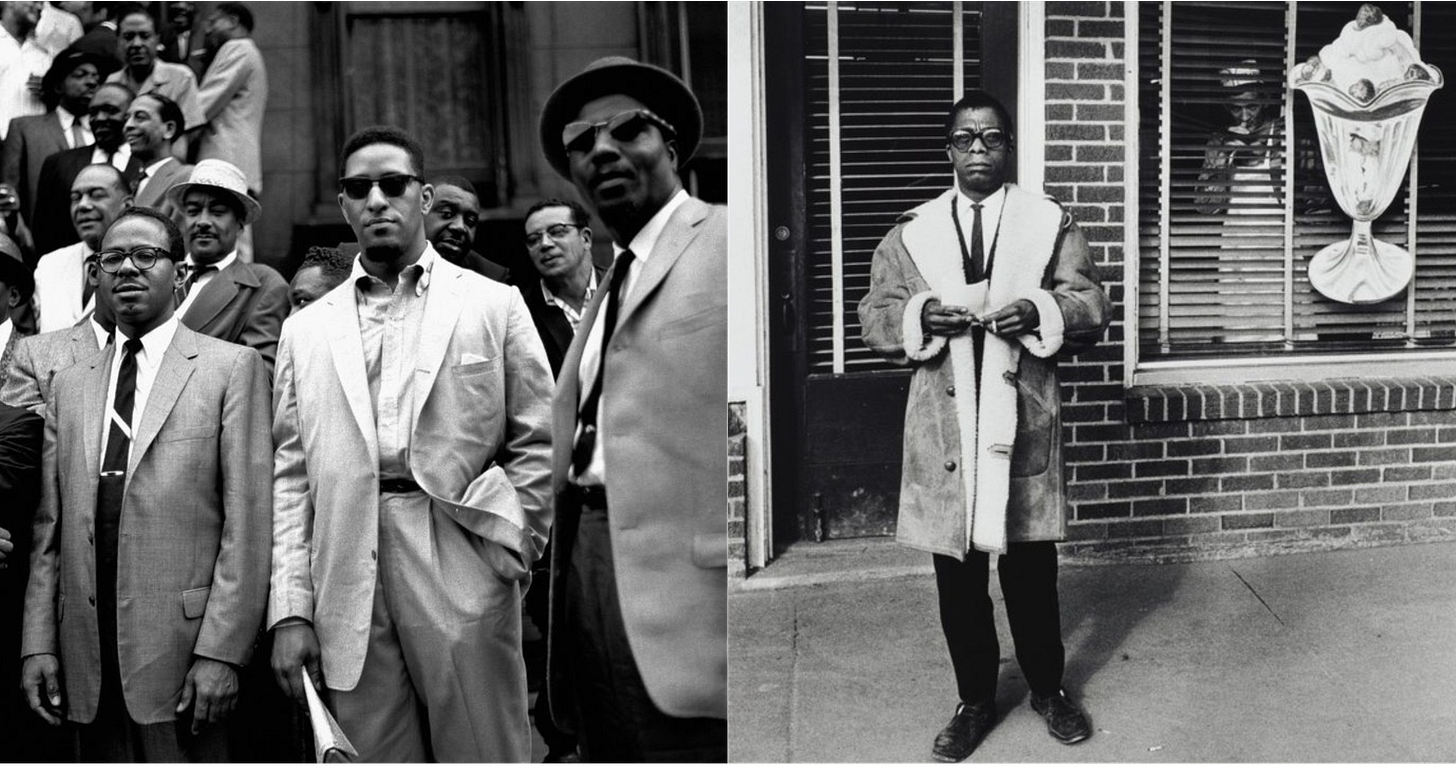

Using style as a tool for agency isn’t just a pretty idea. In Black Ivy: A Revolt in Style, Jason Jules shows how Black men in mid-20th-century America adopted and transformed Ivy League style into a language of protest, dignity and aspiration. It’s a striking example of how clothes and styling can assert presence, challenge norms and embody resistance.

By layering Ivy staples with workwear, everyday men turned style into a deliberate expression of belonging, authority and personal agency, questioning assumptions about who belongs.

They didn’t wear Ivy to blend in, but to communicate seriousness and authority. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X used tailoring to assert credibility and challenge exclusion. Others, like James Baldwin and Langston Hughes, used dress to express taste, identity and professionalism. The Ivy uniform didn’t flatten individuality, it created space for it.

Tools for self-fashioning

If we are conscious about what we want to communicate, our clothes can help us express it. Dress codes don't have to be strict or reductive. They can be liberating and supportive.

While it’s a promising idea, it has its limits.

As we learned from my faux pas, you have to learn the script before you improvise. The degree to which we can be creative varies dramatically depending on who we are in the hierarchy.

This is why middle management stick to different hues of baby blue, while those who have risen through the ranks can add some sauce. Perhaps a floral pattern. Or a pair of Louboutin oxfords covered in red Swarovski crystals. Rank buys leeway, which is why they can afford that extra sparkle.

This is not just about title or rank, but the bodies we are born into. My colleagues of colour could not make the same mistakes I did because their margin for error was much narrower.

Yet within whatever constraints we face, we still have a choice to unconsciously follow the script or consciously use it for self-definition. Creativity can live in the details, in fit, styling and how you carry yourself.

How we dress changes how we feel, which influences our actions and the way we live.

It's called enclothed cognition. It’s a psychological concept that describes how clothes don't just cover us, they shape how we think, feel and behave. The physical sensation of the clothes reinforces the symbolic associations of them. Like wearing a shirt that signals seriousness makes us feel professional, or how a day spent in your pyjamas can make you feel…meh.

The way we dress has an undeniable impact on our lives. It’s not frivolous.

Whether we do it consciously or not, aesthetic choices say something about who we are. Use this to your advantage, whatever that is. If it gives you the confidence to move through a room the way you want, it matters.

Looking at the reflection in the changing room, new shirt on, I am trying different ways of rolling the sleeves. I like it crisp but not too neat. My goal is to be bilingual without losing my accent.